I am about to type a sentence I have never before been able to type. I am non-binary. I am non-binary, and my fandom provided me with so much of what I needed to experiment with my gender and arrive at that conclusion. So I’m writing this article as a way to not only explain the link between geek cosplay and culture and gender non-conformity, but also as a way of reaching out with my story, in hopes others might identify, even in some small way.

Okay, this needs a little context. When I was a kid, I had no idea what the term “non-binary” meant. But that’s not saying much. I was a kid! I barely knew what “deodorant” meant. I did know that I was expected to be, or become, a “man,” and that term seemed quite rigidly defined. A lot of it would come to feel very performative, and also quite narrow: you wore sportsball stuff and played a sport, you had access to these aisles in a clothing or toy store, but don’t be caught dead outside of those; you walked, talked, and sat a certain way. I failed at pretty much all of that, and still do, happily.

Of course, IRL, none of that has anything to do with being a “man,” but I wasn’t smart enough to understand that when I was entering puberty. Serious conversations about gender just did not exist in my world at that time. You were what you were labeled, and that was one of two options. That was the truth of my formative years and before. In fact, it wasn’t until graduate school, just over a decade later, that I’d read the narratives of trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people and learn about the vast spectrum that, of course, includes “man” and “woman,” but also so much more.

My first thought when I finally learned about the non-binary identity and the singular “they/them/theirs” was, “Yes! Everyone should be this!” That was, without a doubt, wrong. We need cis and trans men who identify as men, cis and trans women who identify as women, and the myriad people who identify as the 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th genders of so many cultures. People of all genders are working constantly to define, politicize, and feel at home in their identities.

What I really meant was, “I should be this.” I should be non-binary. Something in the autobiographies that I read just sort of clicked. I liked the questioning of gender performances and the fluidity of gender roles. I liked how some uncoupled gender identity from what they wore. A friend of mine recently told me their roommate, who is also non-binary, says, in regard to their style of dress, “It looks like whatever it looks like.” In other words, you can read me as a cis man or a cis woman based on my clothing and affect, but I’m gonna be who I am. Perhaps this is similar to the way religion works for some. I can’t explain, logically, why this all appealed to me on a cellular level, but it did. I can’t really tell you why I’m here saying I’m non-binary instead of saying I’m redefining cishet masculinity. One just feels more true to me than the other, and I say that with huge amounts of love and respect to everyone of all genders.

Absent from my story so far is the other equally important piece of my non-binary identity: my fandom. When I was doing this initial reading about gender identities, almost all of what I read was non-fiction. I read numerous real accounts of actual people tracing their relationships with gender. However, it all sounded so delightfully sci-fi. I mean this with the highest form of respect: Please don’t think I’m trying to say it sounded fictional and far-fetched. Not at all. It sounded so grounded, the way good sci-fi is grounded in some deeper truth. Most of my points of reference as I entered the world of gender fluidity and non-conformity were from science fiction, the same way most of my reality gets filtered through the sci-fi lenses I love.

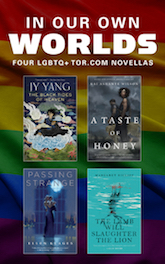

Buy the Book

In Our Own Worlds

The Starfleet uniforms of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, my most sacred sci-fi text, were pretty standard, look-wise, across all genders. That simple fact led me to envision Jadzia Dax and Captain Benjamin Sisko shopping for new jumpsuits in the same aisle of the Space Dillards, which made me immeasurably happy. (For the record, I know this is not at ALL how one obtains a Starfleet uniform in the Star Trek universe.) Jadzia Dax, while not exactly trans or non-binary (I really don’t know any trans or non-binary people that would appreciate the nickname “Old Man” like she does), fascinated me because she contained “male” and “female” identities. Did other hosts contain identities beyond the binary? In my head, I certainly enjoyed imagining. Other Star Trek plots that tried (and, at times, very much failed) to represent gender fluidity and non-conformity comforted me because they at least suggested that I had encountered all this before—I just hadn’t really sat with it and thought through what it meant.

And then there were my action figures. Most action figures are built to represent either a male or a female character. I have not encountered any that are specifically constructed around an explicit non-binary identity, though I’d be thrilled to explore what that would look like. But, as I look at these little plastic folx, there’s a side of them that, to me, screams Judith Butler, screams gender performance. If you ask your Transformers action figure if it’s a man, you probably won’t get much of a vocal answer. (There are those that came with voice capabilities, but “Autobots, Roll Out,” isn’t a gender…or is it?) Instead, they’ve been sculpted to give you certain visual cues that, frequently, point you to a character in some source material that allows you to locate your toy in a gender. Maybe also there’s a file card on the back that uses certain pronouns that also help with this. If we really want to bring in Butler and Simone de Beauvoir, we can also analyze the “active” toy versus the “passive” one (effectively, the action figure and the standard baby doll) and talk about which one is marketed to boys and which to girls.

But the point is: it really does come down to a performance, as Butler often points out. And, if it comes down to the toy’s performance, the role is then pretty easily manipulated by its owner. I make my students play with action figures in my college English class. I hand them toys and tell them to write me the story of that toy. One woman chose, randomly, an action figure of The Rock. She didn’t really know anything about The Rock (other than he was The Rock), so she wrote this story about how there was a really good female wrestler who was stuck inside The Rock’s body, and she would win all these wrestling matches but was constantly pissed off because The Rock would wind up getting all the credit because she was stuck in his body. It was a brilliant story, and there was nothing to stop her from making The Rock into a female character. The toy did not object.

This idea that our genders can, to quote Walt Whitman, “contain multitudes” lines up nicely with how I view my own non-binary identity. This is why I love the singular “they.” To me, it shows that, within the single body, there are many gender forces at work, pulling in many directions. To some that may not ring true for their experience, and to others that may even sound scary, but, personally, it’s exciting. Plus it pisses off old school grammarians even though the singular “they” has been around forever. That’s always fun.

I started giving public lectures on action figures shortly after I started work on my edited collection of academic essays about them, Articulating the Action Figure: Essays on the Toys and Their Messages. I was often quite up-front about my interest in gender representation in toys, and frequently pondered how non-binary identities might be represented in action figures. It was through this that I learned my most important lesson, not from my own work, but from an audience member’s comment.

I was giving a version of this talk to a group of about 50 high schoolers. When the crowd is younger (and, therefore, not as boozed up), I try to shift the conversation toward our favorite toys and the reasons why they’re our favorites. That, then, segues into the conversation about gender and gender bias. Once, after my talk was over, a young high schooler approached me and said, “I wanted to thank you because I’m non-binary and I’ve never heard an adult actually acknowledge that as a thing before.”

I thanked them for revealing that, and assured that student that, yes, it’s most definitely a thing, and you’ve got no reason to hide who you are. That, however, wasn’t technically the first response I had. The first response I had was internal. The first response I had, and I hate that this is true, was my brain silently thinking, “But she looks just like a girl.” I did not ever express that (until now), but I thought about why my brain sent me that message for weeks after. It showed me that, for all my reading and soul-searching, I still misgendered this person internally (referring to them as “she,” mentally), and I still, on a knee-jerk level, equated the non-binary identity with gender performance. It can be about how someone looks, but it by no means has to be, or even necessarily should be. “It looks like whatever it looks like.”

I still feel deeply sorry that I had that response, but my metacognition after my mistake was profound. It allowed me to see, first-hand, that non-binary people don’t have to abide by any particular dress code. That was something I had conceptualized in the abstract before, but that high school student actually demonstrated it. They taught me an important part of being non-binary. While I appreciate their thanks for my talk, it is actually they that deserves all the thanks.

As I continued talking about non-binary identities, young people continued to be my teachers. When I was leading a geek playwrighting workshop at a science fiction convention, one of the participants was a 12-year-old dressed as a combination of Sherlock Holmes and the titular Doctor from Doctor Who. They identified as non-binary, and mentioned that they use the “they/them” pronouns. Again, they were 12. Could I even chew my own food when I was 12? In that moment, I had my doubts. They were their with their father and sister, who were nothing but supportive. The workshop was then greatly enhanced by this participant because, now, an out pre-teen non-binary person was exploring what it was like to put non-binary people into sci-fi narratives. While I hope I led this workshop effectively, I can assure you that they were the leader. I left immensely inspired.

In both instances, it wasn’t just that young people were identifying as non-binary, it was that young geeks were identifying as non-binary. Even I, as I mentioned before, found solace in dovetailing the non-binary identity and sci-fi in my head. So I had to ask: why? Why were non-binary identities and geek identities so often turning up in the same places, and, often, in the same bodies?

When Colorado-based non-binary theatremaker Woodzick created the Non-Binary Monologues Project, I was able to explore this question in depth. I wrote a geeky monologue for Woodzick’s project, and later, asked Woodzick if they might want to bring a collection of geek-themed non-binary monologues to Denver Comic Con for a special performance. (I co-run Denver Comic Con’s literary conference, Page 23.) Woodzick rapidly assembled a team and put together a show, TesserACT: Dimensions of Gender (or Queernomicon at Comic Con). The show ran to great acclaim in early June, and will be presented at Denver Comic Con on June 15th. This show demonstrated that, yes, in fact there were more people out there actively exploring the link between gender identity and fandom.

When I asked Woodzick about this, they said, “Geek fandoms can be a gateway or an escape hatch for discovering new facets of one’s self or trying on different identities. Our script supervisor, Harris Armstrong, wrote a line in a monologue ‘Gender expression through robots made us feel gender euphoria…This was our place to play with who we were without making anything seem permanent.'” I like this notion because it reminds me that I found my own “place to play” not through robots but at Comic Cons. I have enjoyed (and still enjoy) creating cosplay costumes that put my assigned male body into that of a traditionally female character. To me, that allows me the opportunity for some degree of gender play, and requires no explanation. At cons, there are hundreds of fans doing the same sort of gender/costume play, and for different reasons. For some, gender is irrelevant; they’re fans of a character, and that’s that. For others, the gender reversals are acknowledged, but are not in pursuit of some deeper catharsis. For me, there is great meaning in putting on a dress and being Eleven from Stranger Things. I don’t fully conceptualize this as a transgender identity, as, mentally, I don’t feel the need to actualize my womanhood (or my manhood, or, really, any -hood besides personhood). It doesn’t have the exaggerations that come with drag. It just makes me feel less like one thing, and more like many. “It looks like whatever it looks like.”

Comic Cons have given me space to express this through many performances and many costumes, and I’ve done so basically without harassment. That lets me view cons as a sort of haven for all forms of gender expression, and maybe invites me to think about why I’ve encountered so many non-binary geeks. Cons give us the floor to experiment, judgement-free. But this is, on some level, a delusion. Of course there’s harassment. Of course there’s judgement. When my friend Ashley Rogers, a trans woman, went to New York Comic Con a few years ago, she did not go in cosplay. She was there in an official capacity as press. While she was working, a stranger approached and lifted her skirt, violating my friend’s privacy and attacking her senselessly. Furthermore, misgendering still happens, and, while I currently use both “they” and “he” pronouns, other non-binary people need to distance themselves from their dead names and assigned genders for very serious mental health reasons. Because I present, often, as a cis man who is also white, I have to check the privilege that comes with that. To assume cons are filled with infinitudes of understanding and love would be to erase the pain felt by those I cannot ever pretend to speak for. Non-binary folx who are people of color, non-binary folx who are read as cis women, trans people—my words should never override any of their experiences, some of which have been horrifyingly negative. When I asked Woodzick what geek culture might learn from non-binary people, they said, “The biggest upgrade would be to have more non-binary and trans representation in new characters that are being created.” That might, one would hope, help to curb the kind of violence and harassment that my friend suffered, but there’s no way to say for sure. It certainly couldn’t hurt. If there is a great amount of geek love in the non-binary community, maybe it is time more shows went the Steven Universe route and explicitly included more non-binary and trans characters.

With Denver Comic Con opening having taken place this past weekend, that pretty much brings us up-to-date on my non-binary self. I believe, strongly, that my fandom plays a huge role in my gender story. I believe there are connections even more subtle than what was explored here. I believe plenty of what I wrote will be scoffed at by those who think this is all just a passing trend. (It isn’t.) But I know there are more people out there—perhaps at cons, certainly beyond—asking themselves tough questions about their gender identity. If this is you, and you happened to have stumbled on this piece: be you. Wear the thing. “It looks like whatever it looks like.” The real question is: how does it feel?

Jonathan Alexandratos is a New York City-based playwright and essayist who writes about action figures and grief. Find them on Twitter @jalexan.

A rather light response here, but the first time I heard of Non – Binary, my immediate thought was “Hey! *I* want that T-Shirt too!”

“No, not that.

No, not that either!”

Thanks for this, article.

As someone trying to learn: is there clear difference between non-binary and androgyny? Is it “neither” vs “both”?

I am reminded of a line from Lost Horizons about how a little politeness all around can resolve problems. Simple courtesy, people. If somebody is in a dress and wants to be called she it doesn’t hurt you to accede to their wishes. Same with other behaviors and pronouns. Whatever your personal opinion of the issues it’s right to be courteous.

@3: Thanks so much for your question! I wish more people would ask these earnest questions as opposed to ones like, “Y U GOIN 2 HELL THO????” While the answer to your question is much more fluid than I’m going to make it sound (<–said every gender theory person about everything ever), here are the essentials: “androgynous” or “androgyny” often constitutes less a gender category and more a type of appearance, usually an appearance representing gender ambiguity. I resist saying androgyny is a combination of “both” genders because “both” implies “two,” which is exactly what non-binary people resist. It’s true, though, that many androgynous people you see will be performing a blend of the traditionally masculine and the traditionally feminine. (As an aside, the prefix “andro-” comes from the Greek for “man,” but it has come to mean “human,” therefore suggesting that androgyny is less concerned with categorization into a single gender and more interested in approaching a “human” identity.) Annie Lennox often appears on lists of androgynous people, though by all accounts she identifies as female and uses the pronouns “she/her/hers.” Plenty of non-binary people embrace an androgynous look, too, but they by no means have to. This is where the difference lies: because “non-binary” is a gender identity, it does not carry with it a “look” or singular appearance (as there are many ways to perform all genders). I know some non-binary folx who prefer androgyny, but I also know plenty who don’t, and are often read as cis men or cis women. Personally, I’m most comfortable wearing clothes assigned masculine and feminine, which may put me closer to androgyny, look-wise, but I think I’m mostly read as a cis man, whether in or out of that costume. However, none of that changes the fact that I am non-binary, which is why I like that “It looks like whatever it looks like” sentiment expressed by my friend’s roommate. So, TL;DR: androgyny is built around a look or appearance, the non-binary gender identity is not. Sorry for the long response!

Very interesting read, non-binary characters have long been a staple of sci-fi and fantasy. But I do find it interesting that sections of the modern left have embraced the concept of gender. My understanding is that gender is a society’s or culture’s expectations of the sexes. So in many cultures a man is supposed to be “masculine” whilst a woman is supposed to be “feminine”. But no one can ever meet such cultural exceptions: everyone, regardless of sex, exhibit both “masculine” and “feminine” characteristics. In a real sense everyone is “gender fluid”.

@@.-@: I actually think that the situation regarding the use of gendered pronouns and the issue of misgendering is far more complicated than politeness.